Amy Savage (left) shows me where to wield the electric ant aspirator.

Gathering ants in the city is a curious way to pass a few hours. I can’t say I’d ever given a thought to ant gathering. But on a mild mid-October day, I joined biologists Holly Menninger and Amy Savage, in a green island in the middle of Broadway to look for, and collect, ants.

Amy Savage seeks ants in a Broadway median near 106th St.

I tend to look up and out when I walk, alert to the presence of urban birds and mammals like squirrels or raccoons. I scan trees, the sky, water towers, building ledges, the Riverside Park retaining wall. Seeking ants turned my gaze downward to the earth, and focused it narrowly on small patches of ground. My abilities as an ant collector are, to put it gently, undeveloped, but my few hours spent looking for ants has yielded an expanded appreciation for how much life is unfolding in small patches of ground beneath my feet. In a sense, my neighborhood has expanded.

Worlds within worlds: ant collectors in NYC, look for creatures below our feet.

But back to ant collecting.

Holly Menninger

Holly Menninger is an entomologist and Director of Public Science at Your Wild Life, a team of scientists interested in “exploring the ecological frontiers that exist right under our noses, from the surface of our skin to our backyards and neighborhoods.” Based at the University of North Carolina in Raleigh, Your Wild Life conducts a variety of research projects.

I first saw Holly at the Arnot Forest in Ithaca, NY a little over a year ago. I was attending NY State Master Naturalist training, and she was one of our lecturers. She gave a lively lecture on invasive species with a particular focus on an invasive marine plant that, transported unknowingly by boat owners, was threatening the waterways. More recently, we met through the internet after Holly had moved to North Carolina when, in preparation for up-coming field trips to New York City, she started following NYC nature blogs, including Out Walking the Dog.

Amy Savage

Amy Savage is an ecologist who studies ants and their beneficial relationships with other insects and plants. Her research on ant mutualisms has taken her to Samoa, New Zealand, Australia, Costa Rica, Panama, Washington State as well as New York City.

I was thrilled when I learned that Holly and Amy would be gathering ants in NYC, and not just anywhere in NYC, but in my neighborhood within steps of my front door. Needless to say, I joined them.

Here are a few things I learned about ant collecting that you may not know.

1. On a warm, pleasant day in mid-October, collecting ants is quite an enjoyable activity.

Amy and Holly among the trees in the median on Broadway between104th and 105th Streets.

2. Ants are partial to Pecan Sandy cookies, which are considered the gold standard for ant bait.

Pecan Sandy crumbs await devouring ants.

Apparently, Pecan Sandies have just the amounts of sugar, salt and fat that ants love. Still the cookies Amy and Holly had laid out in the medians did not seem to be attracting ants on this day.

3. Real scientists, like Holly and Amy, suck ants. Let me explain. They use a tool called an aspirator which works through suction.

You breath in through a rubber hose, drawing ants up through a nozzle at the other end into the clear collecting jar at the center of the contraption. You are protected from the bits of soil, and other debris that come with the little guys by rubber gaskets that seal off the plastic chamber. Even so, Amy wasn’t too happy on an earlier trip to Broadway medians when she learned that pesticide, said to be rat poison, had been sprayed on plants in the median. (She was even less happy when a rat fell to her feet from a tree while she was collecting.)

4. Faux scientists, scientists-for-a-day, like me, are guided away from the breath-activated aspirator to an electric aspirator. This operates by means of a simple switch rather than human breath. Yet even this very simple machine takes a little time to figure out how to use effectively. I’d spot an ant or two, aim my aspirator and then jab my thumb around in a futile attempt to find the on-button without losing sight of the tiny, well-camouflaged ants. In these early stages of my ant-collecting apprenticeship, quite a few ants escaped my scientific grasp, disappearing into grass or soil before I could get my machine working.

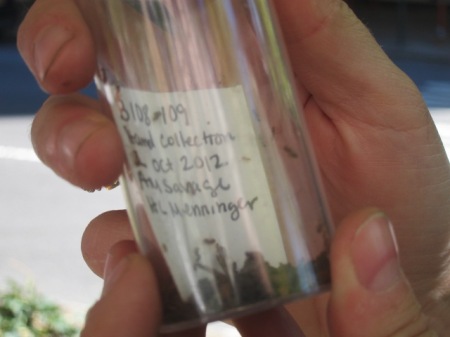

Ants in the collection jar, all labeled and ready to go.

Sometimes the way to get the ants is a gentle and judicious use of tweezers.

Tweezing ants.

We spotted other small creatures, as we searched. Snails, for example, and lots of roly polies, or pill bugs. Roly polies belong to the family of wood louse known as armadillididae, which roll up into tight little balls when threatened. This marvelous rolling-up behavior is given the equally marvelous name of “conglobation.”

Roly polies and a pretty snail.

Here is another collection of animals, found on the underside of a rock, that include roly polies and other creatures I do not know.

Roly polies and other small animals.

A bright orange spider.

Orange spider in its web.

A millipede.

Millipede.

And aphids.

Aphids.

We shared the median with members of our own species as well.

The median is a multiple-use miniature park, and its users come from many species.

Amy on the hunt.

Amy and Holly were indefatigable.

Holly at work.

But after a couple of hours, I said good-bye to return to my work.

Later in the day, Holly and Amy apparently hit the ant bonanza in Riverside Park, where ants were plentiful. The next day, they were joined in Morningside Park by Georgia, who writes NYC’s Local Ecologist blog.

Now they’re back in North Carolina, where the ants will be categorized and their DNA will be analyzed.

In a future post, I’ll tell you why these scientists are studying NYC ants, what they’re hoping to learn, and how you can contribute to their research as a citizen scientist.

Meanwhile, visit School of Ants for more on ants and citizen science.